What We Know about the Literacy Development of K-2 Black Boys?

Literacy skills set the foundation for academic success. Unfortunately, systemic barriers can sometimes prevent students – including young Black boys – from developing their full potential as readers, writers, and speakers. In our recent project funded by Amazon and in partnership with the National Girls Collaborative Project, Dr. Rebekah Degener at University of Mankato, and Terysa Ridgeway from Terysa Solves It, we investigated literacy development of Black boys through a systematic literature review. Below, we present highlights of our recently published journal article: A Systematic Literature Review of Literacy Development of K-2 Black Boys.

Systematic Literature Review

We conducted a review of the academic literature in order to better understand the landscape of literacy development of Black boys in kindergarten, first, and second grades by answering the question: What does previous research indicate about how the U.S. education ecosystem fails K-2nd grade Black boy’s language arts interests and abilities?

Our search of three different academic databases and rounding out those searches with an expert consultation resulted in 46 studies. We considered how these studies were framed (that is, did they blame young students for systemic factors?), what topics they focused on, and what study results found.

What We Found

Our analysis identified seven key themes addressed across the literature:

- literacy skills assessment: some studies found the current assessments are appropriate for all children, while others did not

- the impact of the use of Black English: use of Black English did not harm literacy skills development

- inclusive and culturally relevant curricula: appropriate curricula can better support students’ skill development

- interventions and pedagogical approaches: a variety of interventions are represented in the literature and show promise, including the use of readers theater

- professional development: quality professional development emerged as a key factor in supporting students’ literacy development

- student engagement: some practices, such as prescriptive curricula, may inhibit student engagement; other practices, such as high expectations, can better support it

- the research agenda: our work confirms previous studies that indicate that, given the importance of the topic, there is an insufficient research base

Recommendations

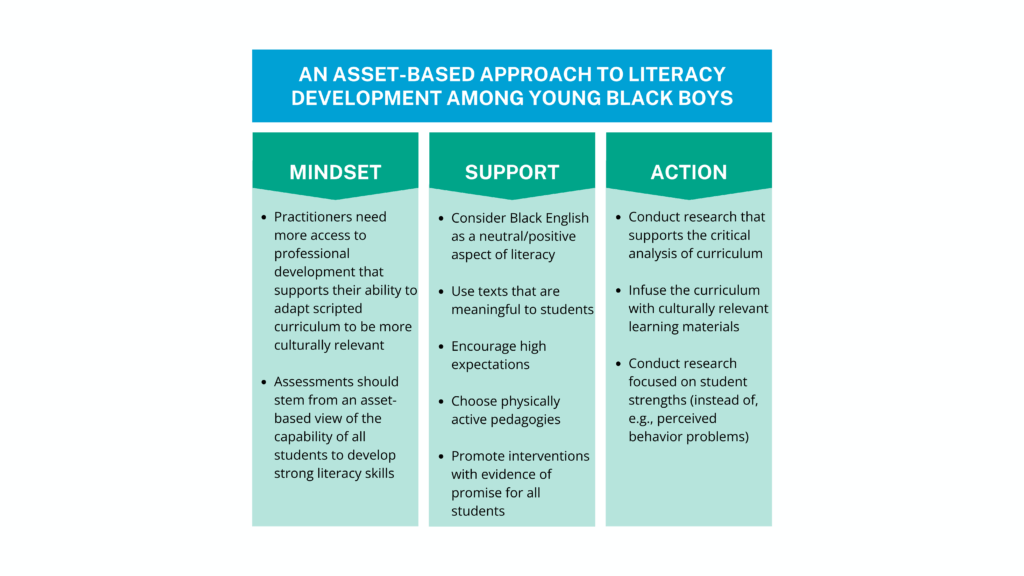

Our recommendations support an asset-based approach that emphasizes the abilities of young Black boys to flourish academically when appropriate support is provided.

This asset-based approach involves more support for practitioners to adapt curriculum to meet the needs of all students. It also involves support for practitioners to adopt assessments that embody an asset-based viewpoint. Educators can better support young Black boys by viewing Black English as a neutral or positive aspect of literacy. In addition, using meaningful texts, encouraging high expectations, and choosing physically engaging pedagogies will engage Black boys. Our literature review also found that more research is needed, particularly research that focuses on leveraging students’ strengths.

Acknowledgement

This work was funded by Amazon Future Engineer.

Citation

Smith, J. M., Thigpen, L., Degener, R., & McGill, M. M. (2025). A Systematic Literature Review of Literacy Development of K-2 Black Boys. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 17(3), 405–416. Retrieved from https://www.iejee.com/index.php/IEJEE/article/view/2416